The idea of the atomic number was created by Henry Moseley, who also contributed to the initial understanding of an atom’s structure by scientists.

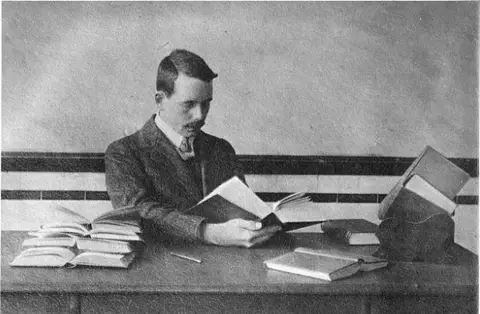

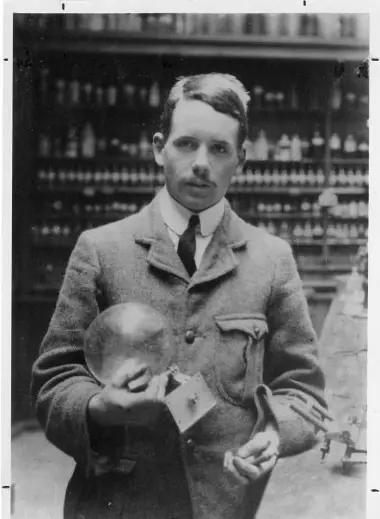

Credit: Smithsonian Archives Courtesy

Henry Moseley, a physicist, was exempt from participating in World War I.  ,

The young Moseley’s mother advised him to use his scientific knowledge from behind the battle lines because he was an accomplished scientist and an aristocrat.  ,

Moseley, unfazed, attempted to enlist in the Royal Engineers of the British military but was initially turned down. We need engineers, not physicists, they told Moseley.

Nevertheless, he eventually took over as their second lieutenant and oversaw a 26-man command.  ,

A bloody battle at the Gallipoli peninsula in the Ottoman Empire ( present-day Turkey ) claimed the lives of about 1,000 British soldiers a few months later, early on August 10, 1915. Britain and its allies suffered a catastrophe when Gallipoli was invaded.  ,

Moseley, who was shot in the head and passed away instantly, was one of those killed. About three months before turning 28 years old, he was 27.

However, Moseley’s contributions to the periodic table of the elements had already had a long-lasting effect on science even when he was young.  ,

When I was reading Richard Rhodes ‘ book The Making of the Atomic Bomb in 2008, I learned that Moseley had died at the Battle of Gallipoli. Moseley was depicted in the book wearing a uniform.  ,

I developed a strong interest in learning more about Moseley’s passing, his contributions to science, and how he came to be fighting in this conflict. I had previously been to the Gallipoli battlefields four times and had always been fascinated by the conflict’s history.

Credit: Miral Dizdaroglu’s politeness

This conflict reflects both my background and my line of work, which is why I find it fascinating. I’m a scientist who was born in Turkey. It’s crucial for us to keep in mind the contributions made to the periodic table, especially on Periodic Table Day, as my work and the work of many scientists depend on it.  ,

Gallipoli is a lovely and tranquil location, and I’ve had the good fortune to visit it several times. In their memoirs, some British soldiers who made it out of Gallipoli claimed to have heard nightingales singing.  ,

In a friendship gathering between Turkish and British organizations honoring this battle, as well as with several Turkish universities, I had the chance to speak about Moseley. The Turkish Academy of Sciences, where I had spoken about Moseley, even asked me to write a small book about him.

Because Colonel Mustafa Kemal ( Atatürk ), who led Turkish soldiers to victory in that battle and others, later founded the secular Republic of Turkey, Gallipoli marked a turning point in Turkish history. Additionally, he served as Turkey’s first leader.  ,

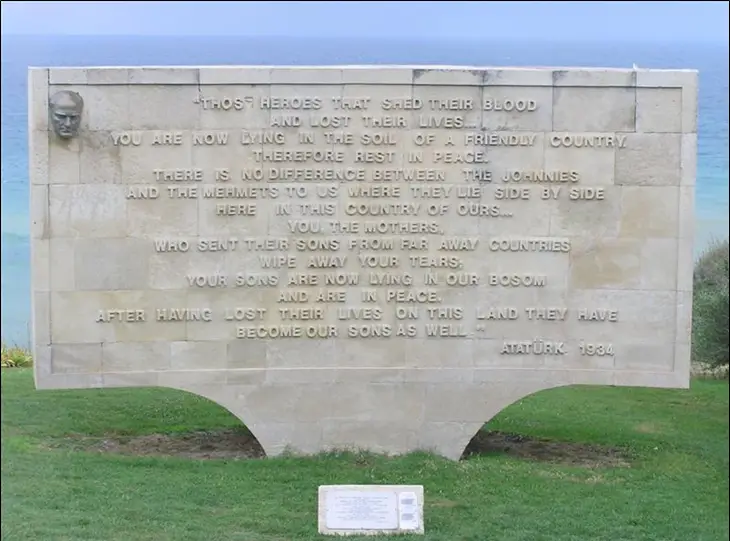

Mustafa Kemal ( Atatürk ) erected a memorial in 1934 to honor every foreign soldier who had died in Gallipoli. He uttered the following words in writing, which were later carved into a stone memorial:

” those brave individuals who died and shed blood.” You are currently lying in a friendly nation’s soil. So, have peace of mind. Where they now coexist in this nation of ours, there is no distinction between the Johnnies and the Mehmets. Your sons are now lying in our arms and are at peace, and you, the mothers, who sent them to distant countries, wipe away your tears. They have also become our sons after dying on this land.

Credit: Miral Dizdaroglu’s politeness

The British went back to the Gallipoli peninsula after the war and buried the dead soldiers ‘ remains there. Most were impossible to pinpoint.  ,

There are probably hundreds of other unidentified soldiers interred alongside Moseley. Around the British-built Helles Memorial on the peninsula, the names of the fallen British soldiers are inscribed in stone. Second Lieutenant Henry Gwyn Jeffreys Moseley of the Royal Engineers is one of them.  ,

Early Life and Education of Moseley, nbsp

On November 23, 1887, Henry Gwyn Jeffreys Moseley was born in Weymouth, England. He was born into an affluent and noble family that included eminent scientists. Henry Nottidge Moseley, his father, was an Oxford University professor of anatomy and physiology. When Henry’s father passed away in 1891, he was only 4 years old. Amabel Gwyn Jeffreys, a Welsh biologist’s daughter, was his mother.

In 1910, Moseley graduated from Trinity College at Oxford University with a bachelor’s degree. After that, Moseley enrolled in University of Manchester classes under Professor Ernest Rutherford. In 1908, Rutherford was awarded the Chemistry Nobel Prize. It was like a “nursery of genius” in his lab. Young researchers from various nations who built the majority of contemporary atomic physics were employed by Rutherford. They all won their own Nobel Prizes, many of them.

Moseley developed an interest in the nature of X-rays, which were first discovered in 1895, while collaborating with Rutherford. Moseley was certain that finding distinct X-ray wavelengths for each known element would provide science with a potent chemical analysis tool. He thought it might reveal some of the atom’s structural secrets. It turned out that Moseley was correct.  , ++

The Elements Periodic Table and Moseley’s Contributions ,

We are aware that the periodic table depicts all of matter’s chemical constituent parts. These 118 blocks are collectively referred to as chemical elements. The number of protons in an atom’s nucleus is equal to the atomic number for each element.  ,

Welcomia/shutterstock .com is the source of credit.

However, there was only a periodic table with 63 elements at the time of Moseley’s research. This version was created in 1869 by Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. The weight of the elements ‘ atoms, also known as their atomic weight, was how they were arranged at the time.  ,

The idea of an atomic number did exist in 1869, but it was arbitrary. It was merely a periodic table element. There was no evidence linking the atomic number to any quantifiable physical quantity. In Mendeleev’s table, chemists had already found that the atomic weights ‘ order was reversed three times by the chemical order. This phenomenon could not be adequately explained.

The idea that the elements were arranged incorrectly in the table was advanced in 1913.  ,

To test this theory, Moseley constructed an X-ray machine and used it to examine the characteristics of 12 elements. Later, he expanded on this work by incorporating gold and aluminum elements. The equations between the frequency of the elements “X-ray spectra” and the atomic number were established in three papers where he published his findings. Moseley provided scientists with the quantifiable physical property required to arrange the periodic table more precisely by measuring X-ray frequencies.  ,

Credit: Smithsonian Archives Courtesy

Moseley’s Law is the name given to these equations. Moseley predicted four unknown elements by leaving four empty lines in one of the graphs from his most recent paper that showed the relationship between the X-ray frequencies and the element atomic numbers. These components were found by other scientists after his passing.

The number of protons in an atomic nucleus was determined by Moseley’s research.  ,

The study of light absorption and emission is known as spectroscopy, and Moseley laid the foundation for the use of X-rays in chemical analysis.  ,

On a plaque on the Clarendon Laboratory at Oxford University, Moseley’s work is exquisitely summarized:

H. G. J. Moseley finished his ground-breaking research on the frequencies of X-rays released from the elements at the Clarendon Laboratory between 1887 and 1915. His research helped to clarify the atom’s structure and established the idea of an atomic number. He established the foundation for a significant tool in chemical analysis by predicting several novel elements.

The Legacy of Moseley

Rutherford wrote,” Moseley was one of the best young people I ever had, and his death is a severe loss to science,” when word of his passing reached Manchester.

Given that other scientists have also perished in battle, many in the scientific community criticized Britain’s use of brilliant minds.  ,

Rutherford wrote to Nature,” It is a national tragedy that our military organization was initially so inflexible as to be unable to use the offers of services of our scientific men except as combatants on the firing line,” This young man’s death on the battlefield is a glaring illustration of how scientific talent is misapplied.

During World War II, the lesson was partially learned. The British military organization assigned scientists to covert work during that conflict.

Additionally, Winston Churchill, the battle’s architect, was fired as First Lord of the Admiralty following the Gallipoli battles ‘ misfortunes.  ,

However, during the World War II assaults in Normandy on June 6, 1944, both the American and British navies applied the lessons they had learned from Gallipoli. Additionally, Australia and New Zealand gained their independence as a result of the Gallipoli campaign, which promoted their sense of national identity.

In his brief life, Moseley published eight papers, which is his scientific legacy. Physics and chemistry made significant strides thanks to Moseley. The Nobel Prize was given to other scientists who made significant discoveries during the same time period.  ,

According to many of Moseley’s coworkers, the Nobel Prize would have been awarded to him soon if he had lived. In actuality, Karl Manne Siegbahn, a physicist who continued Moseley’s planned research and methodology after his passing, was awarded the 1924 Nobel Prize.  ,

I frequently ponder what Moseley might have done if Gallipoli had lived to see him change the periodic table, one of the most important concepts in physics and chemistry. We’ll never know, but I’m happy to contribute in some small way to ensuring that Periodic Table Day and every day are remembered of him.  ,

- The Reflexion of the X-Rays, by Henry G. J. Moseley and Charles G-Darwin, Phil. Mag. 26, 210–232, 1913

- The High-Frequency Spectra of the Elements, by Henry G. J. Moseley, Philadelphia Mag. 26, 1024- 1034, 1913

- The High-Frequency Spectra of the Elements, Part II, by Henry G. J. Moseley, Phil. Mag. 1914, 27, 703- 713.

- Anchor Books, Doubleday &, Company Inc., New York, 1971; Bernard Jaffe, Moseley, and The Numbering of the Elements.

- The Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology by Isaac Asimov, published in 1972 by Anchor Books, Doubleday &, Company Inc., New York.

- The Life and Letters of an English Physicist by John L. Heilbron, H. G. J. Moseley, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1974, University of California Press

- Historical Studies in Atomic Structure Theory by John L. Heilbron, Arno Press, New York, 1981

- The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes, Simon &, Schuster, 1986, New York.

- The Periodic Table: A Story and Meaning by Eric R. Scerri, Oxford University Press, 2007.